Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

The idea of Japan as an ethnically and culturally homogenous country is a pervasive one, both in Japan and across the world. For foreigners, the idea of Japan as a homogenous country is pretty ingrained – and for most Japanese (as any expat in Japan will tell you), the sight of a person of non-Asian descent speaking Japanese is still cause for incredulity. Obviously, this doesn’t exactly scream that Japan’s a country of Diversity!

(As a side note – this experience also gets old pretty quickly for the tiny minority of non-Asian native Japanese speakers living in Japan. Watch some of Ken Tanaka’s videos for a funny perspective on what it’s like to be a “Kei Nihon-jin” – someone who was born and raised in Japan but is not ethnically Japanese)

There is also a political dimension to the myth of Japan’s homogeneity: it fosters a sense of national identity, contributing to the strong Japanese sense of cohesion. For this reason the Japanese government has traditionally endorsed the misconception. A sense of national unity does have important benefits, but it also has the effect of forming a barrier against the world – keeping the outsiders out and the insiders in.

In reality, of course, what constitutes “outsiders” and “insiders” isn’t as simple as you might expect! Japan is more ethnically diverse than most of us realise. Although ethnic minorities in Japan have historically received little to no recognition and have even been actively suppressed – things have changed considerably, and today efforts are being made to preserve and rehabilitate the unique cultures of Japan’s minority groups.

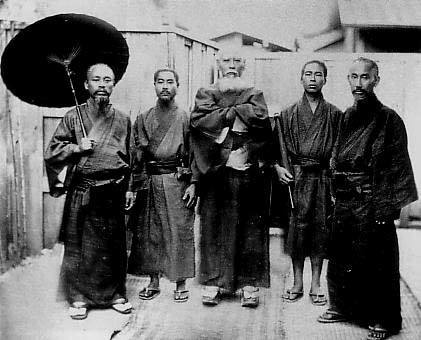

Ainu

The Ainu are the indigenous people of northern Japan and have a culture, language and religion entirely distinct from that of Japan as we know it. During the Meiji Restoration, when Hokkaido was officially incorporated into Japan, Ainu land was confiscated, their language was banned and their cultural and religious practices curtailed. In 1899, they were officially labelled “former aborigines” and granted Japanese citizenship, forcibly assimilating them into the general population in a process that overall took less than fifty years.

From the time of Japan’s unification until 1997, the Japanese government’s official position was that there were no ethnic minorities in Japan – and it took until 2008 for the Ainu to gain official recognition as a minority group. They remain Japan’s only recognised ethnic minority. At this time, the Japanese government also released a statement acknowledging the fact of the Ainu people’s subjugation during the Japanese “modernisation” and expansion.

Today there are very few people of pure Ainu descent left in Japan, but some citizens with Ainu heritage have made attempts to rehabilitate aspects of their culture, traditions and music. One such example is Oki, a musician of mixed Ainu and Japanese descent who plays the tonkori – a traditional Ainu instrument – in the Oki Dub Ainu Band.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_X9QxFaHJwA&w=420&h=315]

Although the damage to Ainu culture can never fully be repaired, Ainu populations in cities across Japan have established political and cultural communities, and there are now institutions whose aim is to protect Ainu rights and heritage – such as The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (FRPAC) run by the Japanese government. The Ainu political party was also founded in 2012, with the aim of realising a multicultural and multiethnic society in Japan.

Ryukyuans

The Ryukyuan people, indigenous to the islands between Taiwan and Kyushu (including modern-day Okinawa), are another sector of Japanese society with culture and traditions distinct from that of mainland Japan.

Preceded by three other Okinawan kingdoms, the Ryukyu Kingdom was a thriving independent dominion from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, participating in trade with China, Southeast Asia and mainland Japan. This long history of trade meant that Ryukyuan culture developed from an extremely diverse group of influences which can be seen in its arts, crafts and architecture.

In the seventeenth century the Ryukyu Kingdom was invaded by Japan and forced into subordination, before finally being officially incorporated into Japan in 1872. More destruction followed in the twentieth century, when the former Ryukyu kingdom became the site of the devastating Battle of Okinawa, and subsequently came under American administration for nearly thirty years.

Despite this turbulent history, and despite Okinawan people having suffered widespread discrimination in twentieth century Japan, Ryukyuan culture has gone on to become something of a success story. Music, dance, art, architecture, textiles and food on the Okinawa Islands are strikingly different from that of mainland Japan, retaining their multicultural flavour and making these islands some of the richest and most diverse areas of the country.

Japanese Koreans

Another significant – and problematic – ethnic group in Japan is the Korean-Japanese population, known as “Zainichi”, who are officially considered foreign residents rather than an ethnic minority. Over the course of Japan’s history, Korea has been instrumental in transmitting the culture and religion of the Asian continent to Japan, and some of Japan’s most treasured crafts were first brought to the country by Korean immigrants. It is even likely that the first Japanese people emigrated to Japan from the area now known as Korea.

Contact between Japan and Korea only became antagonistic in the twentieth century, and many of the ethnic Koreans now living in Japan are the descendants of forced labourers brought to the country after Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910. This population is thought to number in the hundreds of thousands – perhaps even millions – and its members have often faced discrimination despite having lived in Japan for their whole lives.

Although discrimination against ethnic Koreans unfortunately still exists in Japan, through the activism of Zainichi organisations and other minority groups – including the Ainu – the social atmosphere continues to improve. A Korea-Japan friendship festival is now held each year in Tokyo and Seoul to promote better understanding between the two cultures, and Korean food and culture (particularly pop music) is enjoying a surge in popularity in Japan.

Besides the groups mentioned here, there are significant communities of ethnic Brazilians, Taiwanese and Chinese in Japan, along with others.

So there we have it! Busting the myth of Japan’s homogeneity and celebrating its cultural minorities 🙂