Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

Having covered traditional art – from the silk screens of the Heian period to the ukiyo prints of the Edo period – in their first guide, Japan Objects bring us up to the present day with this guide to Modern Japanese art.

Modern Japanese Art

The Japanese art scene today is buzzing with innovation and creativity. We are pleased to share some of the most ingenious craftspeople and contemporary artists, who are often not as well-known internationally as they should be.

The Modern Era

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 was a turning point in Japanese history. Gone with the feudal past and military rulers, Japan marched towards modernisation and westernisation under the leadership of Emperor Meiji.

In the arts, there were significant technological and stylistic developments (thanks to Japan’s newly enthusiastic engagement with the world), in the form of international exhibitions and expositions.

It was in the textile industry where production methods first began to modernise. In the 1860s, Kyoto’s Nishjin – the premier centre of the kimono industry – sent delegates to Europe to bring back the jacquard loom. This transformed weaving processes.

In the field of metalwork, artisans were forced to find other suitable endeavours quickly. The abolition of the samurai class and the prohibition of sword-carrying saw their industry collapse entirely overnight.

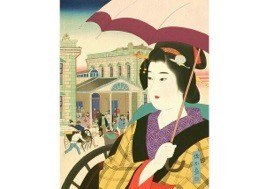

Meiji painters eagerly sought novel ways to reflect the spirit of new Japan. Students, scholars and artists often travelled to Europe or America to bring back Western styles; known in Japan as yōga (western paintings). But for others, the Japanese way could only be captured by building on centuries of national heritage.

These elegant artworks are called nihonga (Japanese painting). Whilst not widely known internationally, theywere created by some of the best Japanese artists to date, such as Shoen Uemura.

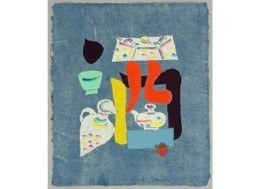

The Meiji era’s unrelenting modernisation was keenly felt by many artists and artisans. The desire for a more ethical and inclusive way of working took hold through the establishment of Mingei, or the Japanese Folk Craft Movement. The aim was to revive struggling vernacular craft industries through formal design study. This was similar to the British Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th century. For instance, print master Okamura Kichiemon was fascinated by the everyday objects of Japanese life, such as the tableware illustrated here, and was the author of many books about Mingei.

The Art of Craftsmanship

Japan’s frenetic modernisation after World War II brought increased prosperity to many, but in the art world, fears arose that Japanese traditional craft skills were drowning under the incoming wave of Western cultural mores.

In response the government enacted a series of laws to encourage and support the arts. This included the designation of important cultural properties, and the informal title of Living National Treasures for master artisans, who could carry traditional skills into the future.

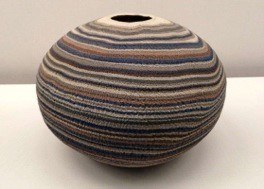

Matsui Kosei (1927-2003) was one such national treasure. By looking at previously extinct craft skills, Kosei was able to develop the neriage technique to fashion intricate and colourful creations like this incredible striated vase.

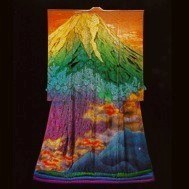

Forgotten techniques inspired artist Kubota Itchiku as well. Through his careful experimentation with a 700-year-old shibori dyeing style, tsujigahana, he turned usually understated items into the canvas for his passionate and emotional art, such as this piece, Mount Fuji and Burning Clouds.

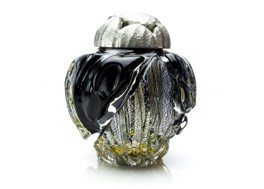

Glass, by contrast, was not commonly used in Japan before the Meiji restoration. However, with the spread of Western-style housing, and windows, artists quickly discovered the potential of such a versatile material. Yukito Nishinaka is one such craftsman working today. Inspired by the Japanese craft objects of the past, Nishinaka reinterpreted items like tea-ware and garden objects, all through the medium of glass.

Art jewellery is another area that, while not native to Japan in its modern form, is able to draw on the country’s rich cultural heritage to produce unique works of art. Mariko Sumioka finds inspiration in the architectural language of Japan; she sees aesthetic value not only in homes and temples, but also in the individual components of the structures: bamboo, lacquer, ceramics, tiles and other traditional craft and building materials.

The Future of Contemporary Art

Japanese contemporary art in the 21st century reflects its creators’ conscious efforts towards innovation and experimentation. Pioneering artists today move swiftly between artistic mediums to express their uncompromising visions. From manga and fashion, to digital sculpture and photography, the accepted disciplinary boundaries are being broken down to make way for artistic and social autonomy.

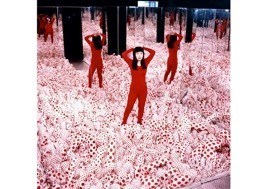

Artistic autonomy rings especially true for the emergence of female Japanese artists. There are an unprecedented number of professional women working in the creative fields, and established artists such as Yayoi Kusama have paved the way for emerging female artists.

Takahiro Iwasaki’s Out of Disorder series is a fascinating example of cutting-edge experimentation; he uses discarded everyday objects to create incredibly detailed miniature cityscapes.

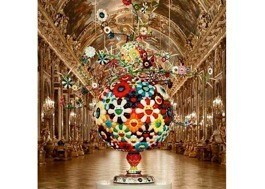

Rule-breaking convictions are thoroughly evident in many of the works of Takashi Murakami. The Flower Matango in the Palace of Versailles is an illustration of the thrilling clash between traditional art and pop culture. By presenting a new hybrid of these influences, Murakami takes his place as one of the most thought-provoking Japanese artists working today.

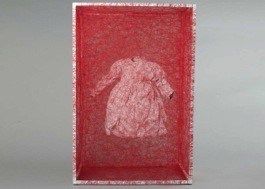

Berlin-based artist Chiharu Shiota has a distinctly pertinent vision of artistic innovation. She creates large-scale installations exploring states of anxiety and remembrance. State of Being, for example, is a stunning portrait of the powerful connections between people and their belongings. By encasing everyday things, like a child’s dress, in infinite webs of red yarn, she transforms ordinary objects into evocative personal memories.

About Japan Objects

Japan Objects is an online magazine for culture lovers, presenting the most inspiring Japanese art & design through informative articles and tailor-made travel guides.

In the UK and interested in Japanese art? We are delighted to be sponsoring Bristol Museum’s Masters of Japanese prints: Hokusai and Hiroshige landscapes exhibition between 22 September 2018 – 6 January 2019 – see you there!